Alzheimer's Disease

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease is one type of dementia. It is a progressive and eventually fatal disease of the brain. It impairs higher brain functions such as memory, thinking and personality. The cause of Alzheimer’s disease is unknown and there is no cure. Current research is focusing on prevention, treatment and cure of the disease.

Two types of Alzheimer’s

The two forms of the disease are familial Alzheimer’s disease, which is caused by a rare genetic mutation, and sporadic Alzheimer’s disease, which can strike anyone. Sporadic Alzheimer’s disease affects one in 25 Australians aged 60 years and over.

Alzheimer’s disease causes changes in the brain

How the Brain and Nerve Cells Change

|

|

|

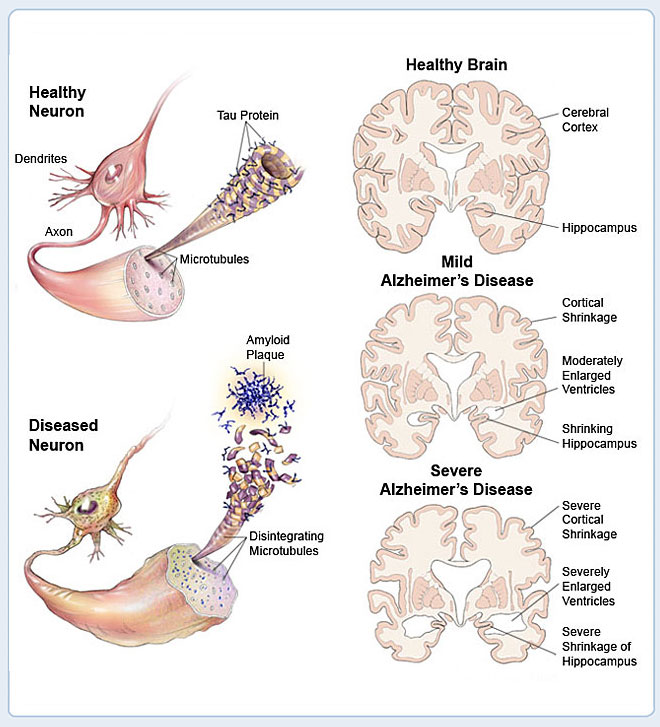

Brain cells or neurones ‘talk’ to each other through connections called synapses. In Alzheimer’s disease, these connections are broken and ultimately disappear in the parts of the brain where thinking occurs.

Research has found that people with Alzheimer’s disease have damaged brain cells, called ‘tangles’, and deposits between the cells, called ‘amyloid plaques’. These plaques are mostly made up of a protein called ‘A-beta’ or beta amyloid. A build-up of this otherwise normal protein is thought to cause the damage.

Sometimes the beta amyloid protein can convert oxygen into hydrogen peroxide – a form of bleach – which then corrodes or ‘rusts’ brain cells, particularly the parts of the brain concerned with memory and reasoning. Researchers are trying to work out why this build-up of amyloid plaques occurs in some people and not others. They are also trying to find ways to reduce or abolish the toxic effects of this protein.

Established risk factors

The cause or causes of Alzheimer’s disease are not known. However, some risk factors have been identified. Well-established risk factors for Alzheimer’s include:

- Age – the risk of developing Alzheimer’s doubles for every five years over age 65. For people aged 70–74 years, there is a 1 in 30 chance, compared to a 1 in 3 chance for people aged 90 to 94 years.

- Genetic history – early-onset Alzheimer’s is a very rare form of the disease that can occur in people between the ages of 30 and 60. In the 1980s, researchers found that changes in certain genes cause early-onset Alzheimer’s. A person has a 1 in 2 chance of developing early-onset Alzheimer’s if one parent has any of these genetic mutations.

- Genetic conditions – most people with Down syndrome over the age of 40 will develop Alzheimer’s disease at a relatively early age. The reasons are unknown.

Possible risk factors

Other risk factors for Alzheimer’s have been suggested but not all have been proven. Some possible risk factors include:

- Head injury – especially more severe head injuries.

- Head size – people with a smaller head may be at a higher risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

- Vascular risk factors – factors that affect the vascular (blood vessel) system may also increase the risk of Alzheimer’s; these may include things such as smoking, hypertension and diabetes.

- Diet – a diet high in saturated fats may increase risk.

Research into treatments

Research into Alzheimer’s is focused on four possible treatments:

- Increase the efficiency of the damaged nerve cells – the drugs currently used are tacrine hydrochloride (Cognex) and donepezil hydrochloride (Aricept). They bolster the efficiency of the nerve cells most affected by Alzheimer’s disease. However, the effects are short lived and don’t cure the disease.

- Prevent production of beta amyloid proteins – researchers have searched for molecules which inhibit the ‘parent’ molecule of the beta amyloid protein, to reduce the production of the proteins.

- Protect nerve cells from the damaging effects of hydrogen peroxide – studies using vitamin E have shown small but significant improvements in function in one group of Alzheimer’s disease sufferers. Researchers are testing a range of antioxidants to see if they help protect nerve cells.

- Inhibit the build-up of beta amyloid proteins – researchers believe that beta amyloid proteins may become toxic as they build up. If the accumulated proteins could be broken down, they may be less harmful.

Research into risk factors and prevention

Many areas are being researched as possible risk factors, which may help identify ways to delay or prevent the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. Areas of research include:

- Cholesterol

- High blood pressure

- Diabetes

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- Gender and hormones

- Brain activity

- Physical activity

- Antioxidants and nutrition.

Cholesterol

Some research has suggested a connection between high blood cholesterol levels and a higher risk of Alzheimer’s. This caused researchers to ask whether drugs that lower blood cholesterol might also lower the risk of Alzheimer’s. The most common drugs used to lower blood cholesterol are called statins. Some recent studies have shown a lower risk of dementia in people who take statins but other research has been inconclusive.

Other research has found that a high level of the amino acid homocysteine is associated with an increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s. High levels of homocysteine are known to increase heart disease risk.

High blood pressure

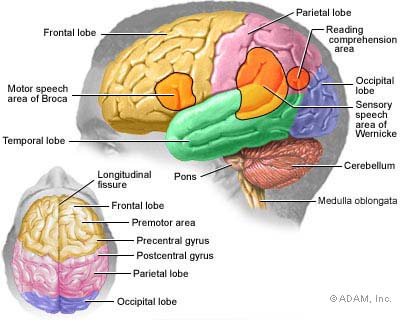

There may be a link between high blood pressure, other stroke risk factors and Alzheimer’s disease. High blood pressure and other stroke risk factors – age, diabetes, cardiovascular disease – can damage blood vessels in the brain and reduce the brain’s oxygen supply. This damage may disrupt nerve cell circuits that are thought to be important to decision making, memory and verbal skills.

Diabetes

Studies show that diabetes is associated with several types of dementia including Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia (a type of dementia associated with strokes). Alzheimer’s and Type 2 diabetes share several characteristics, including deposits of a damaging amyloid protein – in the brain for Alzheimer’s and in the pancreas for Type 2 diabetes. Scientists are learning more about the possible relationships between these two diseases.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are analgesic (pain-killing) drugs used for a variety of conditions. Some studies suggest an association between a reduced risk of Alzheimer’s and the use of certain NSAIDs such as ibuprofen, naproxen and indomethacin. However, clinical trials have so far not demonstrated a benefit from these drugs.

NSAID drugs such as ibuprofen should not be taken regularly as a preventative measure against Alzheimer’s. The abuse of NSAIDs carries significant risks including stomach irritation, gastrointestinal bleeding and possible interaction with other medication.

Gender and hormones

It is known that women have a higher risk than men of developing Alzheimer’s disease, even allowing for the longer average lifespan of women. Researchers are examining the effect of various hormones on the brain, including oestrogen.

Some studies have suggested that women who take oestrogen-based hormone replacement therapy (HRT) have a lower risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease, while one recent study suggested a higher risk where oestrogen levels are low in the brain, not just in the blood. However, another study has shown that the risk of dementia does not reduce with oestrogen-only HRT, and increases slightly with combination oestrogen and progesterone therapy.

Brain activity

Keeping the brain active is associated with reduced risk of Alzheimer’s, but it is not yet clear why this is the case. Research is looking into:

- Mentally stimulating activities and how they might protect the brain. It is thought that these activities might help the brain become more adaptable and flexible in some areas of mental function so that it can compensate for declines in other areas.

- Reduced involvement in intellectual stimulation, which could reflect very early effects of the disease.

- Other lifestyle issues. People who regularly engage in mentally stimulating activities might have other lifestyle features that may protect them against Alzheimer’s.

Physical activity

Research in animals and humans has shown that both physical and mental function improve with aerobic fitness. For example, some research has found that walking was particularly beneficial. In one study, a walking group became more physically fit than those who were assigned to a stretching and toning group. The walkers also showed greater improvements on tests of planning, scheduling and decision making.

Antioxidants and nutrition

Research is continuing into the role of nutrition and nutritional supplements in Alzheimer’s disease. Areas of research include:

- Antioxidants – these may protect brain cells against the damaging effects of hydrogen peroxide as beta amyloid proteins break down. Vitamin E has shown some promise, but very high doses of vitamin E (above 1,000 units per day) can actually increase the risk of having a stroke. The herbal supplement gingko biloba is also being investigated for its antioxidant properties, but there is no evidence that it will cure or prevent Alzheimer’s.

- Fats in food – a high intake of saturated fats increases the risk of diabetes, hypertension and other vascular conditions, which are thought to be associated with Alzheimer’s. Research is investigating how diet interacts with Alzheimer’s.

- B-group vitamins – people with low levels of folic acid (folate) or vitamin B12 appear to be at higher risk of Alzheimer’s disease. A deficiency in either vitamin may allow an increase in the levels of an amino acid called homocysteine, which is known to be a risk factor for heart disease.

- Sage – the herb reputedly boosts memory. It has been shown that sage acts as a cholinesterase inhibitor, the same behaviour shown by three drugs licensed for Alzheimer’s disease.

- Aluminium – there is no evidence that aluminium in the diet or environment increases the risk of Alzheimer’s, but research is continuing.

Vitamins and herbal supplements can have powerful side effects and interact with other medication. Discuss taking any supplements with your doctor first.

Steps that may help prevent dementia and Alzheimer’s disease

It is not possible to cure dementia. There is no proven way to prevent dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease. However, research has shown that some measures may reduce the risk by either delaying or preventing the onset of dementia.

Many of these steps have proven health benefits for other conditions, even if they do not ultimately protect against Alzheimer’s disease. Suggestions include:

- Avoid head injury – always wear a seatbelt and use protective headwear for sports.

- Monitor and lower cholesterol and homocysteine levels.

- Monitor and control high blood pressure.

- Control diabetes and maintain a healthy weight.

- Limit saturated fats in your diet.

- Enjoy a diet high in antioxidants from fruits and vegetables.

- Maintain adequate dietary vitamin E and consider supplements (not more than 400mg a day) on the advice of your doctor.

- Maintain adequate B12 and folic acid intake and consider supplements on the advice of your doctor.

- Enjoy a moderate alcohol intake if you drink alcohol.

- Maintain social and intellectual activities.

- Exercise regularly.

- Don’t smoke.

Where to get help

- Your doctor

- Alzheimer’s Australia Tel. 1800 639 331

- National Dementia Helpline Tel. 1800 100 500

- The Mental Health Research Institute of Victoria Tel. (03) 9388 1633

- Your local community health service

- Your local council

- Aged Care Assessment Services (contact via DHS) Tel. (03) 9606 0000

Things to remember

- The cause of Alzheimer’s disease is not known and there is no cure.

- Research has identified many risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease.

- Activities that may prevent or delay Alzheimer’s disease will also benefit your overall health.

10 warning signs of Alzheimer's:

1. Memory loss. Forgetting recently learned information is one of the most common early signs of dementia. A person begins to forget more often and is unable to recall the information later.

What's normal? Forgetting names or appointments occasionally.

2. Difficulty performing familiar tasks. People with dementia often find it hard to plan or complete everyday tasks. Individuals may lose track of the steps involved in preparing a meal, placing a telephone call or playing a game.

What's normal? Occasionally forgetting why you came into a room or what you planned to say.

3. Problems with language. People with Alzheimer’s disease often forget simple words or substitute unusual words, making their speech or writing hard to understand. They may be unable to find the toothbrush, for example, and instead ask for "that thing for my mouth.”

What's normal? Sometimes having trouble finding the right word.

4. Disorientation to time and place. People with Alzheimer’s disease can become lost in their own neighborhood, forget where they are and how they got there, and not know how to get back home.

What's normal? Forgetting the day of the week or where you were going.

5. Poor or decreased judgment. Those with Alzheimer’s may dress inappropriately, wearing several layers on a warm day or little clothing in the cold. They may show poor judgment, like giving away large sums of money to telemarketers.

What's normal? Making a questionable or debatable decision from time to time.

6. Problems with abstract thinking. Someone with Alzheimer’s disease may have unusual difficulty performing complex mental tasks, like forgetting what numbers are for and how they should be used.

What's normal? Finding it challenging to balance a checkbook.

7. Misplacing things. A person with Alzheimer’s disease may put things in unusual places: an iron in the freezer or a wristwatch in the sugar bowl.

What's normal? Misplacing keys or a wallet temporarily.

8. Changes in mood or behavior. Someone with Alzheimer’s disease may show rapid mood swings – from calm to tears to anger – for no apparent reason.

What's normal? Occasionally feeling sad or moody.

9. Changes in personality. The personalities of people with dementia can change dramatically. They may become extremely confused, suspicious, fearful or dependent on a family member.

What's normal? People’s personalities do change somewhat with age.

10. Loss of initiative. A person with Alzheimer’s disease may become very passive, sitting in front of the TV for hours, sleeping more than usual or not wanting to do usual activities.

What's normal? Sometimes feeling weary of work or social obligations.

The difference between Alzheimer's and normal age-related memory changes

Someone with Alzheimer's disease symptoms |

Someone with normal age-related memory changes |

|

Forgets entire experiences |

Forgets part of an experience |

|

Rarely remembers later |

Often remembers later |

|

Is gradually unable to follow written/spoken directions |

Is usually able to follow written/spoken directions |

|

Is gradually unable to use notes as reminders |

Is usually able to use notes as reminders |

|

Is gradually unable to care for self |

Is usually able to care for self |

STAGES

| Stage 1: |

No impairment (normal function) |

|

|

Unimpaired individuals experience no memory problems and none are evident to a health care professional during a medical interview. |

|

Very mild cognitive decline (may be normal age-related changes or earliest signs of Alzheimer's disease) |

|

|

|

Individuals may feel as if they have memory lapses, especially in forgetting familiar words or names or the location of keys, eyeglasses or other everyday objects. But these problems are not evident during a medical examination or apparent to friends, family or co-workers. |

|

Mild cognitive decline |

|

|

|

Friends, family or co-workers begin to notice deficiencies. Problems with memory or concentration may be measurable in clinical testing or discernible during a detailed medical interview. Common difficulties include:

|

|

Moderate cognitive decline |

|

|

|

At this stage, a careful medical interview detects clear-cut deficiencies in the following areas:

|

|

Moderately severe cognitive decline |

|

|

|

Major gaps in memory and deficits in cognitive function emerge. Some assistance with day-to-day activities becomes essential. At this stage, individuals may:

|

|

Severe cognitive decline |

|

|

|

Memory difficulties continue to worsen, significant personality changes may emerge and affected individuals need extensive help with customary daily activities. At this stage, individuals may:

|

|

Very severe cognitive decline |

|

|

|

This is the final stage of the disease when individuals lose the ability to respond to their environment, the ability to speak and, ultimately, the ability to control movement.

|